Autistic Children Often Have Delayed Speech [1]

In Many Children, These Delays Persist Indefinitely [2]

Talking Is The Result of Many Skills Coming Together Before Age 2

Joint Attention

Looking at and sharing attention with others

Symbolic Play

Using objects creatively in play

Oral-Motor Coordination

Control of speech muscles

Language

Putting words together

In autistic children, these skills often develop late, out of order, or not at all[3]. This leads to delayed or absent speech.

The Good News Is That These Skills Can Be Explicitly Taught [4]

There are many effective interventions. If your child is stuck despite trying, keep in mind that every child is different, and can't talk for different reasons. There is no one intervention that works for everyone.

If something isn't working, try something else. Watch and wait is never recommended. Each intervention could be the key that unlocks your child's ability to benefit from other therapies.

Six Evidence-Based Interventions

You and your child's therapists are likely already doing some of these interventions. The more you know about how and why they work, the better you'll be able to help your child progress.

Joint Attention Therapy[5]

WHAT

Joint attention is how people share experiences using gestures such as pointing, showing, and coordinated looking.

WHY

Joint attention skills, along with nonverbal IQ, are the characteristics most strongly correlated to verbal language skills[2].

HOW

Shaping a point; pausing a song.

Symbolic Play Therapy[5]

WHAT

Symbolic play is a play stage where children begin to use objects to represent other objects.

WHY

The transition from pre-symbolic to symbolic play is critical to the development of language[6].

HOW

Assessing a child's play level, and extending repetitive play to one level above the child's play level.

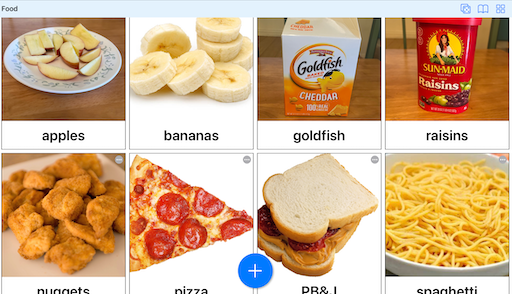

Speech Generating Device[7]

WHAT

A grid of words represented by picture symbols that talk when pressed. Often called "AAC" or "high tech AAC."

WHY

Significantly (50%) boosts frequency of natural speech if child is receiving JA/SP therapy[7]; minimal[8] or uncertain[9] effect on natural speech otherwise, but certainly not harmful.

HOW

Using a minimal grid (<16 words) of words relevant to a play activity, and modelling using the device while talking during play[7].

Language Practice[10]

WHAT

Typically developing children from age 12-26 months form 2-word sentences (Brown's Stage 1) combining nouns, verbs, and adjectives.

WHY

At age 9, 20% of ASD children can say words but can't combine them into sentences; and 25% can say sentences, but not fluently[2].

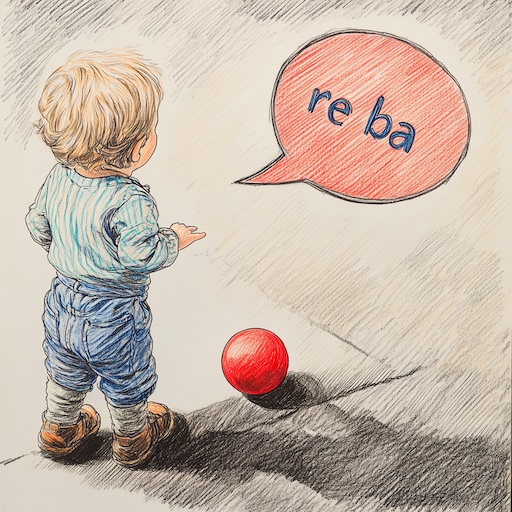

Motor Learning[12]

WHAT

Typically developing children say first words at 12 months. Word intelligibility increases: 50% at age 2, 75% at age 3, and entirely at age 4.

WHY

ASD children often have issues planning and carrying out motor tasks ("praxis"). In one study of minimally verbal ASD children, 24% were identified to have suspected childhood apraxia of speech (CAS)[13].

HOW

Methods like Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cuing (DTTC) use visual, auditory, and tactile cues to teach motor movements, with immediate feedback[14]. Note that apraxia treatment is specialized and current research only supports its efficacy when performed by a trained clinician, not a parent.

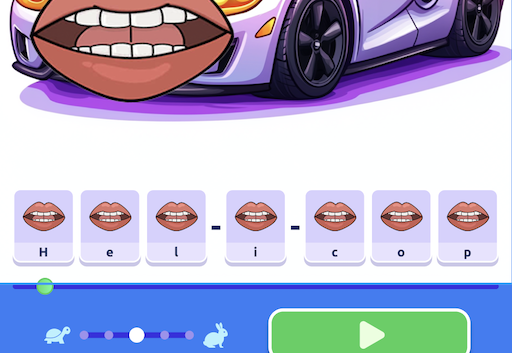

Recommend: Visual Speech

Visual Speech provides visual and auditory cues through animated cartoon lips superimposed on objects of interest. Words are broken apart into tappable phonemes.

Trial: 30 days free OR use Lite Mode indefinitely (5 items, 1 board)

Cost: $5/month

In development

Auditory Motor Mapping Training[15]

WHAT

Babies 6-12 months go through a "babbling and banging" stage, simultaneously babbling while clapping their hands or banging an object in a coordinated manner.

WHY

This integration of vocal and motor systems is thought to help speech develop at a later age.

HOW

In Auditory Motor Mapping Training, a child and clinician try to sing two syllable words together, while the child drums in time with the sung syllables. The intonation and drumming is crucial for the method to work. The method improves minimally verbal ASD children's ability to vocalize syllables and vowels.

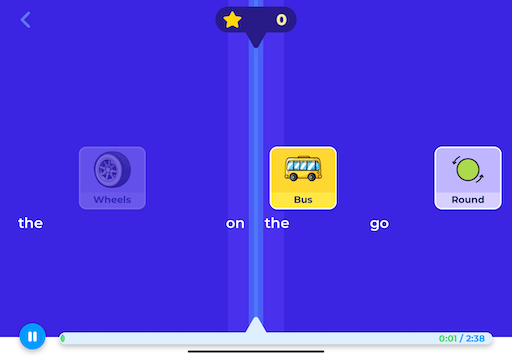

Recommend: Visual Rhythm

Visual Rhythm turns Auditory Motor Mapping Training into a fun rhythm game. Children tap on picture tiles of key words or syllables in favorite songs.

Trial: Use Lite Mode indefinitely (one song)

Cost: $25 one time

In development

References

[1] Howlin, P. (2003). Outcome in High-Functioning Adults with Autism With and Without Early Language Delays: Implications for the Differentiation Between Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(1), 3-13.

[2] Anderson, D. K., Lord, C., Risi, S., DiLavore, P. S., Shulman, C., Thurm, A., Welch, K., & Pickles, A. (2007). Patterns of growth in verbal abilities among children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 594-604.

[3] Paparella, T., Goods, K. S., Freeman, S., & Kasari, C. (2011). The emergence of nonverbal joint attention and requesting skills in young children with autism. Journal of Communication Disorders, 44, 569-583.

[4] National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2023). Minimally Verbal/Non-Speaking Individuals With Autism: Research Directions for Interventions to Promote Language and Communication. Virtual Workshop, January 24-25, 2023.

[5] Kasari, C., Paparella, T., Freeman, S., & Jahromi, L. B. (2008). Language Outcome in Autism: Randomized Comparison of Joint Attention and Play Interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 125-137.

[6] Orr, E. & Geva, R. (2015). Symbolic play and language development. Infant Behavior & Development, 38, 147-161.

[7] Kasari, C., Kaiser, A., Goods, K., Nietfeld, J., Mathy, P., Landa, R., Murphy, S., & Almirall, D. (2014). Communication Interventions for Minimally Verbal Children With Autism: A Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(6), 635-646. Clinical trial registration: NCT01013545.

[8] Binger, C., Berens, J., Kent-Walsh, J., & Taylor, S. (2008). The effects of aided AAC interventions on AAC use, speech, and symbolic gestures. Seminars in Speech and Language, 29(2), 101-111.

[9] Blischak, D. M., Lombardino, L. J., & Dyson, A. T. (2003). Use of Speech-Generating Devices: In Support of Natural Speech. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(1), 29-35.

[10] Binger, C., & Light, J. (2007). The Effect of Aided AAC Modeling on the Expression of Multi-Symbol Messages by Preschoolers who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23(1), 30-43.

[11] Shane, H. C., Laubscher, E., Schlosser, R. W., Fadie, H. L., Sorce, J. F., Abramson, J. S., Flynn, S., & Corley, K. (2015). Enhancing Communication for Individuals with Autism: A Guide to the Visual Immersion System (1st ed.).

[12] Maas, E. (2024). Treatment for Childhood Apraxia of Speech: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 1-26.

[13] Maffei, M. F., Chenausky, K. V., Haenssler, A., Abbiati, C., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Green, J. R. (2024). Exploring Motor Speech Disorders in Low and Minimally Verbal Autistic Individuals: An Auditory-Perceptual Analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 33(3), 1485-1503.

[14] Strand, E. A. (2020). Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing: A Treatment Strategy for Childhood Apraxia of Speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(1), 30-48.

[15] Chenausky, K. V., Norton, A. C., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Schlaug, G. (2022). Auditory-motor mapping training: Testing an intonation-based spoken language treatment for minimally verbal children with autism spectrum disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1515(1), 266-275.